AI Won’t Eat Compilers

In 2011, Marc Andreessen famously wrote an article about why Software is Eating the World. Andreessen’s original article was primarily an argument about businesses, that the largest and fastest growing companies in a variety of vertical markets are software companies, and those companies have or will dominate their sectors. Many company names in that article are indeed market winners a decade and a half later!

These days, others are musing about whether AI will eat software. This is a more nebulous claim. It could mean that AI-centric companies will also come to dominate their sectors. But I’ve had conversations in which folks propose this literally: AI will obviate much software itself. Specialized software, such as apps, search engines, CRMs, etc. will be unnecessary due to the power of general-purpose LLMs, or at the very least, LLMs can just generate bespoke versions on-demand. Whatever you believe about software in general, I argue there is one class of software safe from AI: compilers. The argument I give is that replacing a compiler with an LLM or with an LLM that generates on-demand compiler code is not feasible.

Why Compilers are Different

A lot of software is some state (e.g., in a database), and ways to manipulate the state. There might be a lot of complexity, but effectively, it’s a function

f : Input x State -> Output x State

This is a gross generalization, but sufficient for our purposes. A lot of software, including embedded software, video games, office productivity, etc. fits this model.

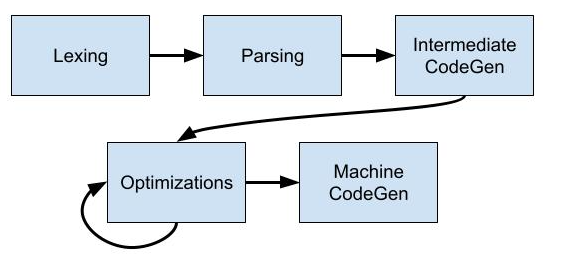

Compare this to a compiler. In the parlance of LLMs, a compiler contains hidden layers, and is the composition of several intermediate functions. The lexer is a function from source code to tokens; the parser is a function from tokens to a parse tree, and so on. The optimizer itself might have dozens or hundreds of passes. It is the composition of all of these functions that maps the input, source code, to output, an executable or libraries. The number of hidden functions and their interdependence is what makes compilers special.

LLMs Today

Asking GPT-5 and Gemini-3 Deep Think to compile a “Hello World” C program results in both saying they can’t, and instead, offering me a script to compile it using Clang or GCC. Spending a little time “bullying” GPT-5 gets it to generate a Python script to generate Arm64 machine code for Hello World, with the caveat that it cannot do the linking required to generate a valid Mach-O executable.

Arguments for Why AI Won’t Replace Compilers

Here are three arguments for why compilers are safe now and in the long-run.

The Reliability Problem. Imagine we reach AGI. A chatbot is the smartest person you know. But even the smartest person you know would be a terrible compiler. Humans are bad at tedium, and compilation is an exercise in tedium. Every stage from lexing, to parsing, to optimization to code gen to linking has to be done exactly correct and with perfect consistency. Humans are bad at that level of rote precise tedium. A compiler is expected to be deterministic; every compilation of the same program with the same flags should result in the same program (well, except when it is not supposed to, like in ASLR). Humans (and AI) reliably are not.

It’s worth taking note of the scale of compiler executions. Every dry-run build in CI/CD invokes a compiler. GitHub reports in 2023 running 15k build jobs per hour. This is a tiny fraction of all the jobs run across all software companies. I suspect many FAANG companies are running several million dry-run builds per day. All that is to say, the reliability for compilation can’t be 99% or 99.9%, but needs to be something well less than 1 in a billion. The name for a compiler that generates bad code any number of times is “a broken compiler”. There’s no path for LLMs to provide the required level of reliability.

The situation today is a little like if we invented monks after Gutenberg invented the printing press and the printed Bible. Everyone gets excited about monks and the cool calligraphy they can do, their intelligence, but when it comes to speed and mass-production, the printing press wins. Compilers are the printing press of machine code generation.

The Cost Problem. The Lua language and compiler is approximately 20k lines of C. Compiling it on an Apple M3 MacBook Air with flags -O2 and -Wall -Wextra takes about 35 seconds of CPU + system time to execute (this includes invoking Make, ~40 invocations of GCC to generate object files & executables, and one invocation of ar to archive). Now suppose we could get an LLM to emulate compilation accurately. Would we want to? No. I can compile 10s of thousands of lines of code locally in seconds, without sending a job off to some data center, without requiring a proprietary model costing billions to train, without hitting my token limit part way through a compilation. Compilers are cheap and fast, and LLMs are slow and expensive.

The Black Box Problem. An LLM is a non-deterministic black-box. If there is a compiler bug causing your program to crash, or an optimization pass that makes your program slower, you can’t figure out what went wrong if the answer is, “Because that is what the LLM decided to do.” Moreover, because compilers are designed as the composition of several small well-defined passes, they are compositional. A black-box makes them non-compositional and difficult to debug or validate.

How LLMs Can Augment Compilers

While AI won’t replace compilers, it can definitely help. Besides the general usage of LLMs as coding assistants, Researchers are using LLMs to discover code optimizations.

Moreover, with the rise of Neuro-symbolic AI, combining LLMs and verification engines, LLMs may be able to generate new optimizations and proofs of their correctness all automatically. For example, a challenge problem for the Neuro-symbolic community to take on would be recreating the results of the paper, Provably Correct Peephole Optimizations with Alive automatically. LLMs and automated reasoning are routinely placing well in Math Olympiads; here is a constrained and important real-world problem to be addressed.

Finally, LLMs can certainly help optimize source programs themselves, helping use better or more efficient algorithms.

Compiler autotuning modifies compiler optimization flags according to a fitness metric (e.g., code size, execution speed). LLMs and ML can help with autotuning. Of course, a compiler itself is a large complex piece of software, and LLM-based agentic workflows can help with automate compiler testing and test-case generation, just as with other software systems.

While I envision that LLMs could enable better compilers, like a lot of software, compilers are here to stay.